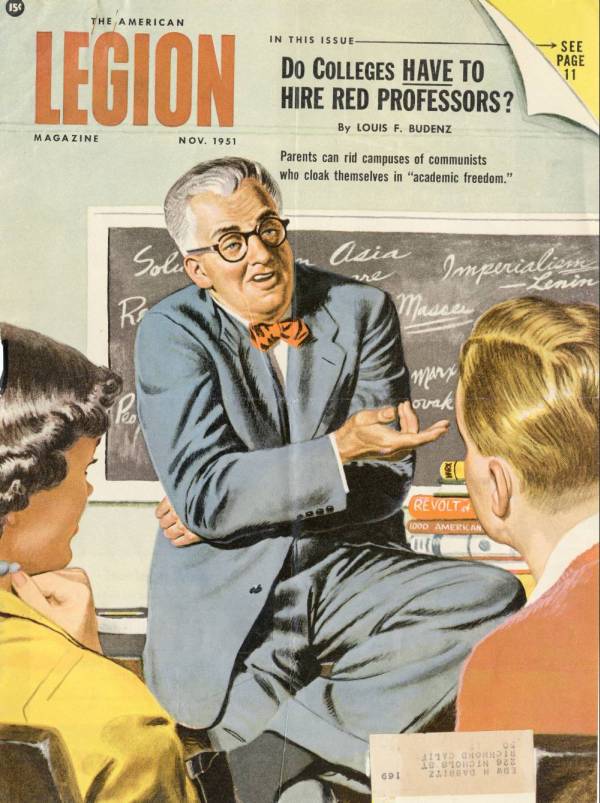

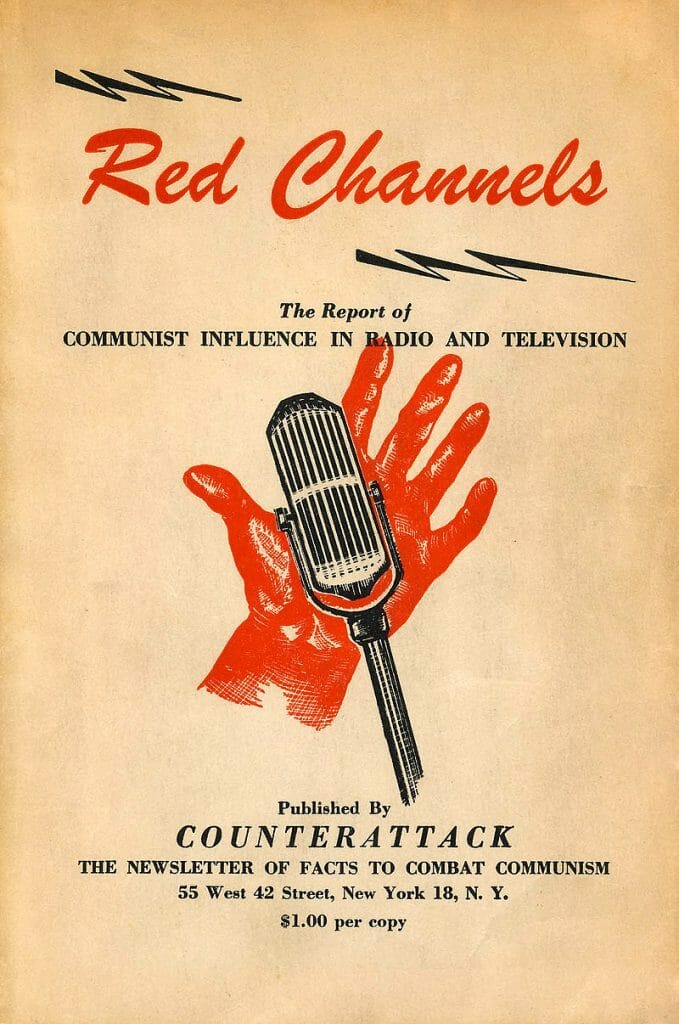

Red Channels was the bible of the blacklist in film and TV. Published by a supermarket executive, with information leaked from FBI files, it detailed activities, like signing petitions or attending conferences, that labelled the subject, like Leo Hurwitz, politically untouchable by networks or studios.

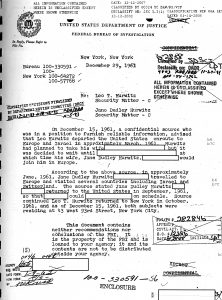

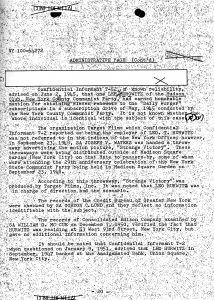

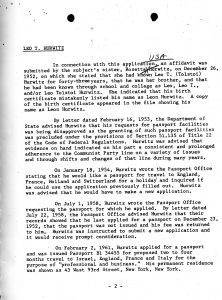

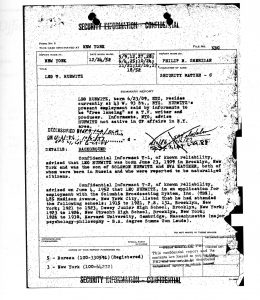

It is hard to know exactly when the US government’s chief organ of political repression in the 20th Century, J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, became aware enough of Leo Hurwitz to keep track of him. The references in its files to his earliest activities, his membership in The Worker’s Film and Photo League, his work as editor of New Theater Magazine both around 1934 come from “reliable informants” but seem to have been entered after the war. Several things, however, are clear. Hoover was obsessed by his concept of the danger of Bolshevism starting in the late 1920’s. After World War II, as the world settled into the threats of the Cold War, the anti-Communism of the far right in America merged with the needs of the political elites to mobilize U.S. public opinion in favor of re-militarization and the containment of the Soviet Union. The dogs of popular fear mongering, not unlike those aimed at immigrants today, were unleashed on the American left wing and anyone who would question the most aggressive anti-Soviet political policies. Leo Hurwitz was watched, his work and travel obsessively notated, his phone calls traced, his family surveilled. Even his grocery list was retrieved from his garbage and entered in his file, which grew to the size of what used to be a phone book. All, because he had ideas and made films.

The 20th Century, as a political epoch, begins in November of 1917 with the Russian Revolution. From that point until the death of the Soviet Communist Party in 1989, the main preoccupation of the capitalist world was what to do about Bolshevism, or the Communist ideology that ruled the Soviet Union. In 1917, Capitalist competition had just brought about the worst war the world had ever known. It came at the end of a series of recessions, twenty-years apart, often called panics, that had periodically driven the lower classes into desperate poverty and threatened the stability of the democratic governments. Shortly after revolutionary Russia had begun to build a system of state welfare, the Western World was thrown into the worst depression it had ever experienced. Whatever the crimes of the Soviet government, it was able to continue growing while the capitalist world lay in economic ruin.

The elites of the world floated a series of ideas as to what to do about this frightening threat. The first semi-successful one, which was tried in Europe and advocated by some academics and industrialists in the US, was Fascism, the militarization of the state and society. The first attempts, most notably Italy, though horrific, drew a great deal of interest (see the letters of Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University at the time). Hitler ran the idea into the ground.

After World War II, it was clear to the thinkers of the present order that the world could not go back to sleep and allow for the expansion of the Soviet Union to be met by political/military inaction and old-style capitalist economics. For the United States, whose population dreamed of peace and quiet, an end to sacrifice and a retreat into its old isolationism, this would mean a new kind of mobilization, both in military buildup and foreign aid. It was called The Marshall Plan and the Truman Doctrine and it looked wildly unpopular. If the political elite wanted these policies to succeed, in the words of Senator Arthur Vandenburg to President Harry Truman, “you’re going to have to scare the hell out of the American people.” Part of that scare was the domestic Red Scare.

Unlike some of its better virtues, America has always been good at finding scapegoats. Witches in New England, the Native Americans as the whites moved west, the African Americans (enslaved and then free), immigrants of every kind from Germans to Mexicans, Chinese to Irish to Jewish, to anarchists (native and foreign born) — fear of all of them and more was used to bolster the support for populist opportunists at one time or another. Fear of Communists as some kind of domestic fifth column of the recent World War II ally and now enemy, Soviet Union, became the next tool. The Marshall Plan was passed by Congress, but the Red Scare gathered over the country like a storm. There had been a few American Communists who had acted as spies for Russia during the war. Therefore all Communists, and anyone who thought like them, were deemed responsible for threatening our American way of life and contaminating our minds.

The key vehicle of repression was not the trial, nor the mob (though these happened), it was the investigating committee.

The key vehicle of repression was not the trial, nor the mob (though these happened), it was the investigating committee. In Congress, there were the Senate Internal Security Committee and the House Committee on Unamerican Activities but every state and many cities had their own anti-communist committees to question suspected leftists, gather names and hound them from their jobs. In fact, Elia Kazan appeared before the House Committee in 1952 and named Hurwitz and his own fellow members of the Group Theater as communists. Hoover’s FBI, now relieved of its job of hunting Nazis and Japanese Americans, and doing very little to keep track of the growing Mafia, swung into action to trace Communists and leftists, whether or not they had done anything more dangerous than advocate ideas. Even without a subpoena to appear before a committee, a visit from two FBI agents to an employer was enough to get someone fired.

In the film and television industries, the anti-communist weapon was an organization, funded by a Buffalo supermarket owner and run by former FBI agents, called Counterattack, and its publication, Red Channels. It was fed a stream of information by the FBI, with an introduction by J. Edgar Hoover. Each broadcast network had its own office, dedicated to cleaning its employee rolls of suspected reds, using the experts from Counterattack to vet its names. Leo Hurwitz began losing jobs around 1951 when visits from the FBI spoiled things at the United Nations Film Office. By the next year, work in the film and television industry was barred to him until 1961.

Another insidious result of America’s anti-Communist hysteria, and one much less understood, was its effect on culture. In academia, all studies that might hint of Marxism were abandoned. In fact, looking at history, economics, sociology from a leftwing point of view could lose a teacher her job. In documentary film, films that expressed an opinion couldn’t get near an exhibitor. Along with the filmmakers who were out of work, the history of our art, with its roots in the left-wing movement, was suppressed. Radical films and filmmakers were too dangerous to write about. An American iron curtain descended over the documentary ancestors and their work. They were never to be fully appreciated or understood by their posterity. Leo Hurwitz and his legacy suffered mightily from a repression that has never fully lifted.

— Essay by Tom Hurwitz, ASC

Pages from Leo Hurwitz’s FBI files