In New York City, in the 1930’s, deep in the Great Depression, a group of around thirty young men, mostly the Jewish sons of immigrants, invented the social documentary film.

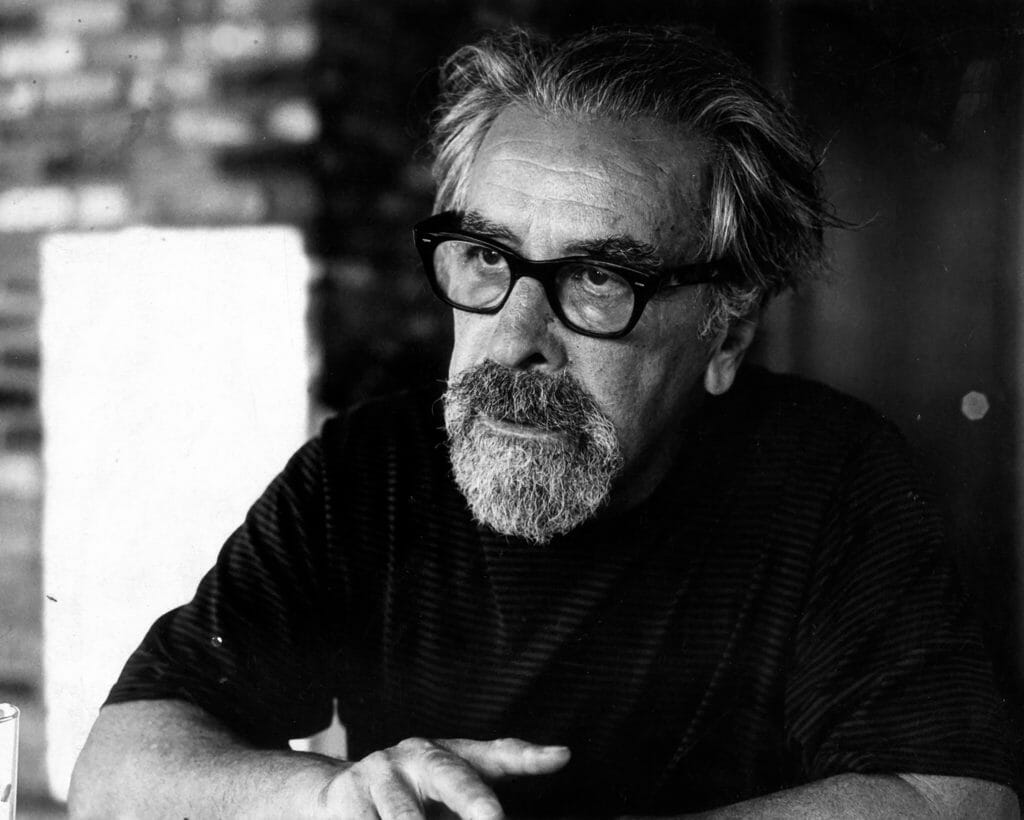

Leo Hurwitz’s contributions to documentary film, as well as those of his collaborators, were central to the birth of the social documentary in the 1930’s. And Hurwitz went on to make great films and singularly important contributions to the development of the documentary and to other film and television styles and techniques, all the way until the 1990’s. Yet Hurwitz’s work and the work of this group of artists, thinkers and technicians was obscured by a kind of iron curtain of political repression that descended over the institutions of the United States during the early Cold War in the 1950’s. The fear of political difference, of anything left-wing that pervaded the country during those years has denied us, who care about the documentary, the memory of our ancestors. The job of this website is to help remedy that loss.

In New York City, in the 1930’s, deep in the Great Depression, a group of around thirty young men, mostly the Jewish sons of immigrants, invented the social documentary film. Central to that group was Leo Hurwitz. But his work and legacy and those of many of his collaborators have been largely left out of the histories of documentary film. This omission is due to the political repression of the 1950’s, which condemned their work, as well as the work of many progressive artists of the time, as “Communist.” To have that label, or even to be considered a leftist, made one dangerous. It was safer for writers and academics to simply evade the contributions of these important documentarians. Another reason for the neglect of Hurwitz and his colleagues is a tendency for film historians to treat individual filmmakers the way art historians would fine artists, each making innovations in an individual way. But film is a cooperative art. It is made by groups of people, making their contributions to the whole project – a phenomenon particularly at play in the development of the documentary film. This historiographical problem also leads to a misunderstanding of how the documentary developed.

Paul Strand is left, Hurwitz directs. Set of Native Land

The film language of the social documentary was forged in the passion of a social movement. These young men, new Americans, educated reared during the boom of the 1920’s. growing up and educated in the promise of America, were faced with its broken promises in the growing unemployment and government inaction in the wake of the Wall Street Crash of 1929. In this time, there was virtually no independent visual medium, no television, only short newsreels that were controlled by the relatively few studios, shown in theaters that were owned by the studios. As these men were drawn to the political left, it became clear that if they wanted news of the growing movements for social change to get out to the public and move beyond the limitations of left-wing newspapers, the relatively new medium of film would be the way.

As they began to form filmmaking groups, collectives like The Workers’ Film and Photo League, they followed the merged culture of the left and of young Jewish men at the time. They debated and argued the theory and practice of film making. They taught classes in it, they had meetings about it, they contended at parties while others danced. They started making newsreels and ended up making documentary films, in the interim inventing the film-form of the social documentary.

Hurwitz films with wide angle lens. Production still, The Big Deep for Standard Oil

From this group, a few young men emerged in leadership and one seemed predominant in both his ability to make films that worked and his ability to articulate why, Leo Hurwitz. From this point on, in the mid 1930’s, here are some of Hurwitz’ achievements:

- He, along with Paul Strand and Ralph Steiner, wrote the shooting script for and photographed the lion’s share of Pare Lorentz’s New Deal sponsored film The Plow That Broke the Plains.

- He and Paul Strand made the brilliantly structured and powerful Heart of Spain.

- He and Paul Strand made the watershed documentary feature Native Land a film that was the first documentary feature to use re-enactments, photo-animation, and complex, interwoven structure.

- After World War II, filmmakers who were influenced by Hurwitz and his colleagues formed the core of the documentary film and television industry in New York, using techniques that were developed during the crucible of the left-wing documentary movement of the pre-war period, even as Hurwitz himself was denied work in that very industry.

- Hurwitz, as Head of Production at the nascent CBS Television Network as well as two smaller television production companies, was central to the invention of multi-camera live television.

- His film, Strange Victory, was the first post-World War II film to counter the kind of home-grown racist and anti-Semitic movements that echoed the ideas of the ones we had fought against. And it warns against the very dangers we are facing in our country today.

- In 1953 Hurwitz’s film, The Young Fighter, made with early portable synched camera and sound equipment, was the first cinéma vérité film. It provided impetus, several years later, for the Drew Unit at Time/Life Films to develop a more portable camera, and then to produce its important cinéma vérité productions.

- His films in the 1950’s and 60’s perfected the styles of photo animation and interview-driven documentary.

- In 1961, he directed the television pool coverage of the entire 6 month trial of Adolf Eichmann, Nazi organizer of the genocide of the Jews of Europe. Held in Jerusalem, it was syndicated world-wide, including in the US.

- He was chairman of the Graduate School of Film and Television at NYU.

We invite you to explore this site, to experience the work of Leo Hurwitz, and to learn more about him.