As head of News and Public Affairs, Hurwitz was central to the invention of live television production in the nascent network

The first recording machines that recorded on tape were stolen from the Nazis in Germany. Enter John T. Mullin and Bing Crosby. Just after the Allies’ victory in Europe, Mullin was investigating a rumored secret German radio-wave ray weapon for the US Army. He came up dry on the ray, but found two big tape recorders and a bunch of recording tape, both of which were virtually unknown outside of Germany. Bing Crosby (no dummy) put up the initial investment to bankroll the Ampex Corporation and its line of tape recorders. A revolution was in the making.

Fons Ianelli, a well-regarded still photographer for Look magazine (among others), saw its possible usefulness for documentary filming at once. He took a big 16mm Auricon camera, a monopod, and his new portable tape recorder, with a crude mic, to the emergency ward of St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York City. There, he filmed and recorded the moans, comings and goings, repartee and ministrations of the denizens of the night shift.

An early modified Auricon camera, blimped for sound and balanced for the shoulder — with Angenieux zoom lens.

The Auricon, a heavy and clumsy affair, was the only “self-blimped” camera of its day. The cameras we have seen in pictures of studio film sets seem larger than they really are, because the basic (noisy) works are surrounded by bloated housings–heavily padded soundproofed “blimps.” Sound was recorded separately on a huge “sound camera,” which produced an optical soundtrack, later married to the picture. All this is an unnecessary precaution when shooting silent (MOS) scenes. Thus 16mm cameras, used for shooting documentaries, industrials, TV commercials and news MOS, were smaller un-blimped mechanisms. The exception was the Auricon, which had internal soundproofing. It was “self-blimped,” mainly for use in filming TV news interviews. The sound was recorded inside the camera (a rare exception), making an optical film track (not tape) right on the edge of the visual film. Because of the low fidelity of the in-camera optical track, this was okay for its very narrow uses. It was fine for speeches and news conferences, but not more subtle conversations or music. And, it really wasn’t very quiet either.

The Nagra III was the workhorse portable, sync tape recorder of first generation of cinéma vérité films

Fons Ianelli mounted this ugly duckling on a one-legged version of a tripod, enabling him to move from place to place with alacrity. Instead of using the limiting internal recording potential of the camera, Ianelli plugged the camera and the recorder into the wall. Since they were now both running on the 60 cycle AC power, they ran at a constant (synched) speed. He was rewarded with footage of a kind never before seen or heard. The sound was close enough to the visual lip movement that the film and the audiotape could easily be adjusted to synchronize in the editing. He had filmed dialogue scenes of real life for the first time.

Ianelli developed the fairly crude system for filming sync sound in the early 1950’s that was used for Emergency Ward and The Young Fighter

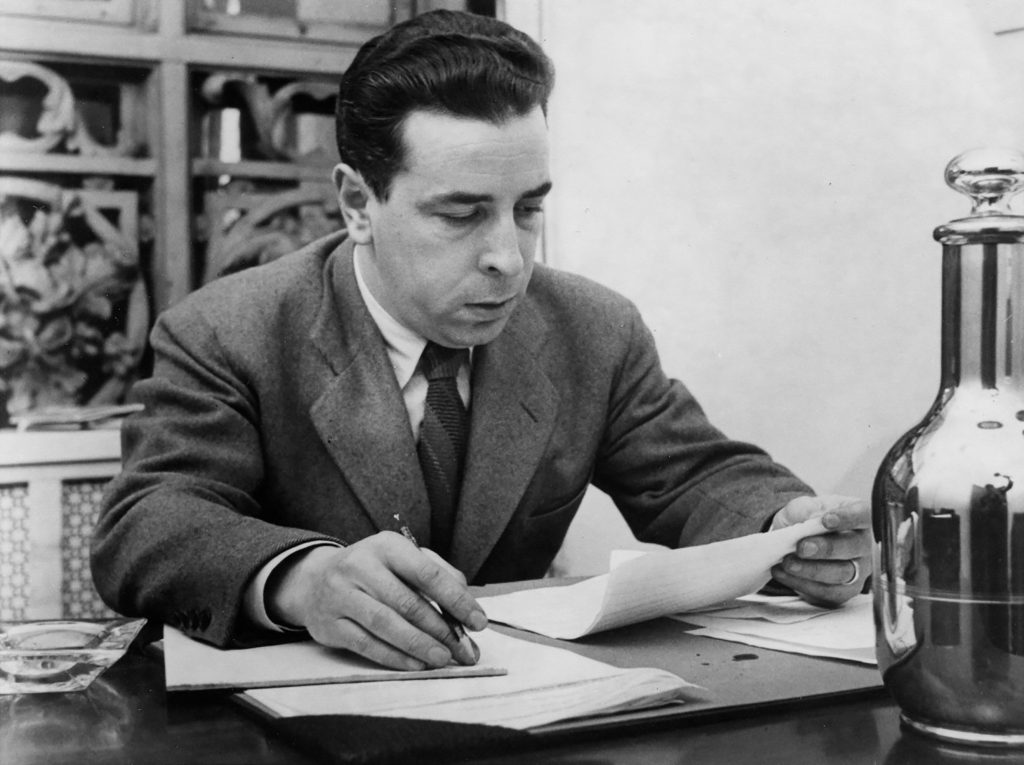

But how to use this remarkable raw material? Ianelli was a still photographer. He had not made a film. He needed to find someone who could turn his random shooting into a viewable entity. He sought out Leo Hurwitz, a renowned documentarian now in straitened mid-career. In the 1930s, Hurwitz with Paul Strand and Ralph Steiner had founded Frontier Films, an independent group devoted to making films that touched the realities of American life. He made a number of remarkable films, including, with Paul Strand, the iconic Native Land. After founding the CBS TV news department and becoming head of production, and then producing films for the United Nations Hurwitz directed the great documentary, Strange Victory, 1947.

Fons Ianelli approached Hurwitz in 1952, the height of the “scoundrel time” of anti-communism, when leftists and liberals alike were under scurrilous attack. Hurwitz was named in a publication called Red Channels, blacklisting him, and making work in the television industry impossible. Elia Kazan, testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee, fingered him along with others he said he knew as communists 18 years earlier.

Hurwitz, accustomed to people coming to him with insoluble film problems, was hired to make sense of the unvarnished miscellany Ianelli had snagged at St. Vincent’s. He had never seen anything like it — raw actuality with sound. The undiscriminating microphone had picked up everything — Yiddish yearnings, Spanish prayer, accented English consoling. The details were wondrous, devastating, magical.

The details were wondrous, devastating, magical.

He devised a coherent order for what became a 20-minute filmed slice-of-life. He hesitated to call it a film, since it had not been planned as one; it had been filmed without a structural plan.

Nevertheless, the resulting Emergency Ward was a stunning and powerful experiment that heralded a new age of filmmaking. The portable tape recorder and portable silent camera – even in this crude form — were the most revolutionary equipment advance since sound came to film; no technological change afterwards so affected the potential of film or video.

Fons Ianelli and Leo Hurwitz formed a partnership called Filmscope. There was a problem, however. If they were going to shop the new technique to the networks, Hurwitz’ role would need to be hidden because of his blacklisted status. Even though he would be co-producer, director and editor, it was Ianelli alone who was visible in promoting their sample film. In 1953 Omnibus, a weekly CBS Sunday afternoon magazine program (before the days of football inundation), commissioned Filmscope to produce five “reality films” using the new technique.

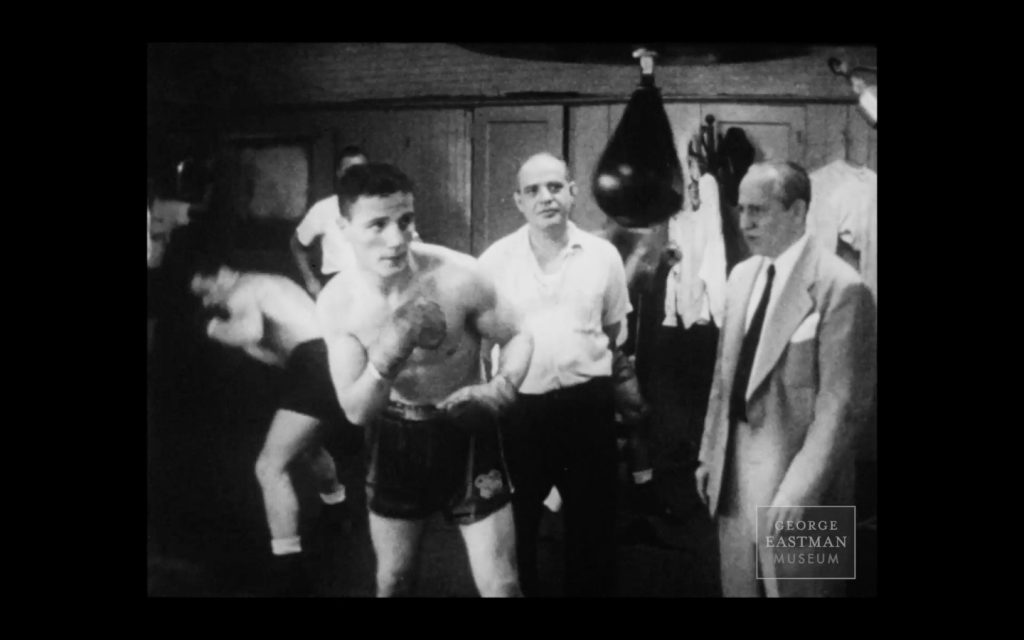

The first of the series was to be The Young Fighter, the real-life story of Ray Drake, an up-and-coming white boxer managed by two men from New York’s garment industry, a manufacturer of fur coats and his “cutter.” The boxer has been training in the city, 250 miles from his wife and new baby, who live in Geneva, NY. He is lonely for them and needs to call them from time to time. When the day arrives for the wife and baby to join Ray in New York, the managers get nervous. Will he be less concentrated on boxing and, most importantly, will the couple’s sleeping together drain him of energy? They call a meeting of the four.

All this was new — the filming of real scenes with sound, from moment to moment in the middle of people’s lives. The challenges were enormous —

All this was new — the filming of real scenes with sound, from moment to moment in the middle of people’s lives. The challenges were enormous — where to put the sparse lights and cables, which scenes to shoot, which not, how not to miss key moments and phone calls without being obtrusive. Since the boxer’s managers often huddled away from the boxer and his family, whom to follow? Ianelli, the sole cameraman, was not a director, and didn’t know about coverage or editing or matching shots or continuity. With a CBS official hovering on the premises, Hurwitz couldn’t be present.

He directed by phone. Ianelli would call, describe the moment, and Hurwitz would tell him what to try to shoot, where to place the camera, what to tell the principals to put them at their ease, what to anticipate.

In 1953, black and white motion picture film stocks were slow, that is, not capable of exposing scenes in dim light. The filmmakers hadn’t wanted to bring many lights to the real locations. In order to increase the film’s sensitivity, the Filmscope team hired Charlie Reiche, a film chemist. When a film is exposed to so little light that nothing shows up after developing, the slight exposure will nonetheless leave a latent effect. It will start the image-making process, and make the film more sensitive. Now, prior to the actual shooting, Reiche pre-exposed the film minimally to bring it to the brink of real exposure. This added one “stop” to the film. It was as if instead of putting ISO 25 film in the camera you put ISO 50. The method was called “latensification,” and Reiche achieved it by running the raw rolls of film in a dark bathroom on the rewind mechanism of a 16mm Bell & Howell projector with only its pilot light on.

To avoid creating static, which would have engraved white starbursts onto the negative, he mounted the projector on a wooden table submerged in a bathtub filled with steaming water. Out came the faster film ready for the next day’s shooting.

The Young Fighter was a fascinating 28-minute human drama. The climactic scene, in which the crude managers harangue the young couple not to sleep together (hilariously implied rather than stated directly), and the wife’s feisty response, was a satisfying resolution to a film whose story and ending had been entirely unpredictable.

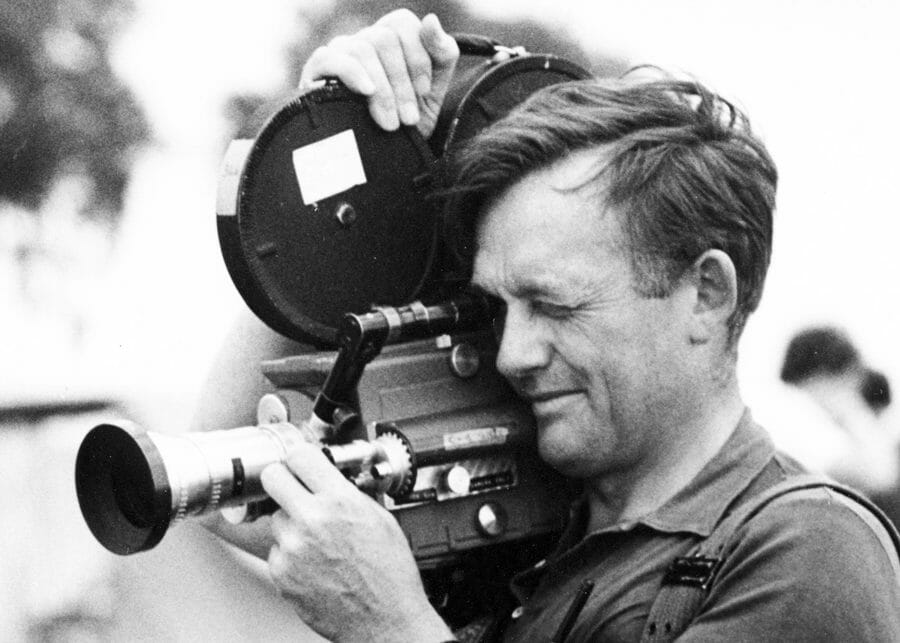

Leacock was a cameraman who joined the Time/Life film unit and helped invent the light-weight hand-held camera for cinéma vérité. He was a significant cameraman and filmmaker in the genre.

Hurwitz and Ianelli had a falling out during the shooting of Deaf Boy, the second film in the Omnibus series. By way of taking over the contract, Ianelli now informed CBS executives of Hurwitz’ disguised role, and reminded them of his leftist background. Hurwitz, who was never officially on the roster, was barred from any further connection with the series. Ianelli hired an editor to do Hurwitz’ work, but because the eventual film was poor and because of the other complications, CBS canceled the remainder of the contract.

In the mid 1950’s, Leo Hurwitz invited Richard Leacock and me to see two of his films, Strange Victory and The Young Fighter. Leacock was a young cameraman friend who had gained a reputation for fine photography in a series of mental health films and, notably, in Robert Flaherty’s Louisiana Story.

It was not the featured Strange Victory that aroused Leacock’s interest that night. The Young Fighter, and the potential of its new form was what excited him. He had already filmed two shorts, Toby and the Tall Corn and Jazz Dance. Both were actuality based, but suffered, as had all other documentaries, from the lack of synch sound. He determined, henceforth, to make films only of that kind, but now to find a way to join real dialogue to picture.

Robert Drew headed the Time/Life film unit that oversaw the development of ightweight hand-held camera-sync sound technology. He also produced the cinéma vérité product of Time/Life Films

At the Time/Life Film Unit, Robert Drew was also conceiving a new kind of documentary, one that would “drop word logic and find a dramatic logic in which things really happened” in real life. He hired Leacock, and also Albert Maysles and D.A. Pennebaker. At Leacock’s suggestion, they screened The Young Fighter. Their imaginations were fired.

With over a million dollars of Time/Life money, the young cameramen, along with an engineer machinist named Mitch Bogdanovich, worked on creating a truly portable camera that could shoot synchronously with the new Nagra 3 recorder, developed by Kudelski in Switzerland. By 1960 they had succeeded in reducing the weight, and quieting the camera. To power it, they developed a battery and an alternator made out of a tiny tuning fork to produce regular AC power. Their first notable project was the1960 Primary, which chronicled the race in Wisconsin between Hubert Humphrey and John F. Kennedy for the presidential nomination. From then on, the nature of the documentary film was permanently changed.

— by Manfred Kirchheimer, edited by Tom Hurwitz