Introduction

During his close to 70 year-long career in documentary films, Hurwitz, made upwards of 40 films, many of them great, and several important contributions to American film and television.

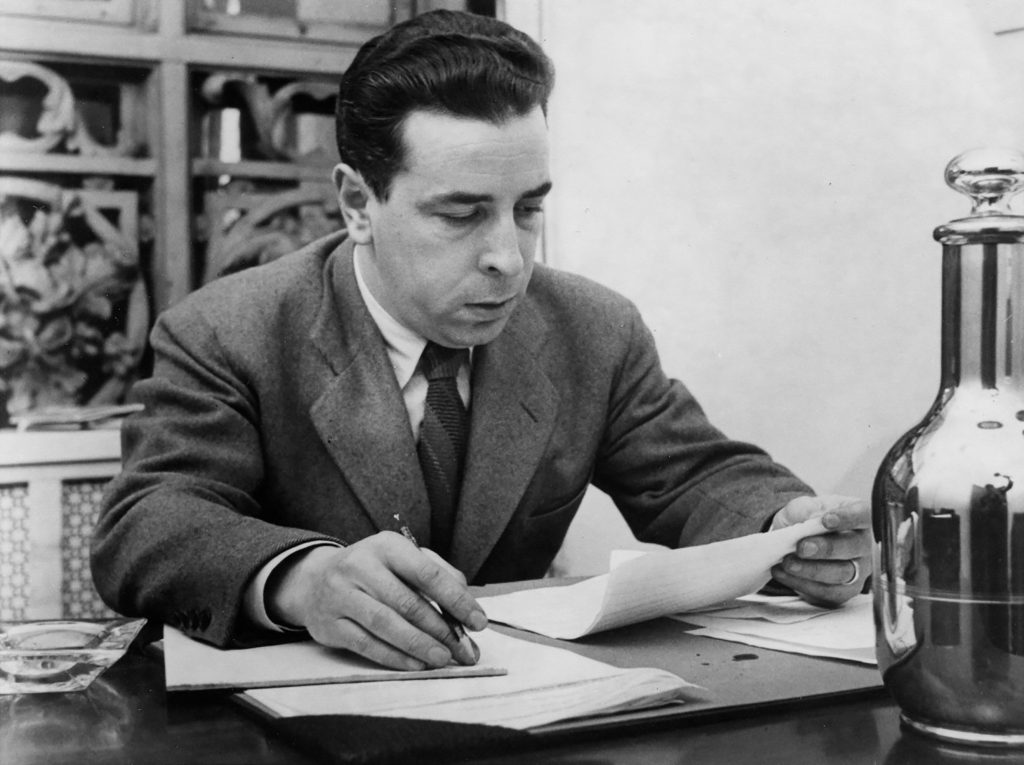

Leo Hurwitz, 1909-1991, was one of the founders of the American documentary film. In the 1930’s, in collaboration with a loose group of other, mainly left-wing film activists, he helped to develop the language of the social documentary, and found the first documentary filmmaking collective, Frontier Films. He collaborated on and directed several of its films, among them Heart of Spain and Native Land. These films exemplified a new way of making films about the real world, and ideas that helps us to understand our world. He and his group saw these films as an antidote to the films of Hollywood that gave the audience dreams of escape from the real world of the Great Depression. Native Land, co-directed with Paul Strand (the legendary still photographer), about the struggle to unionize American industry, opened on the eve of The Second World War, in 1942.

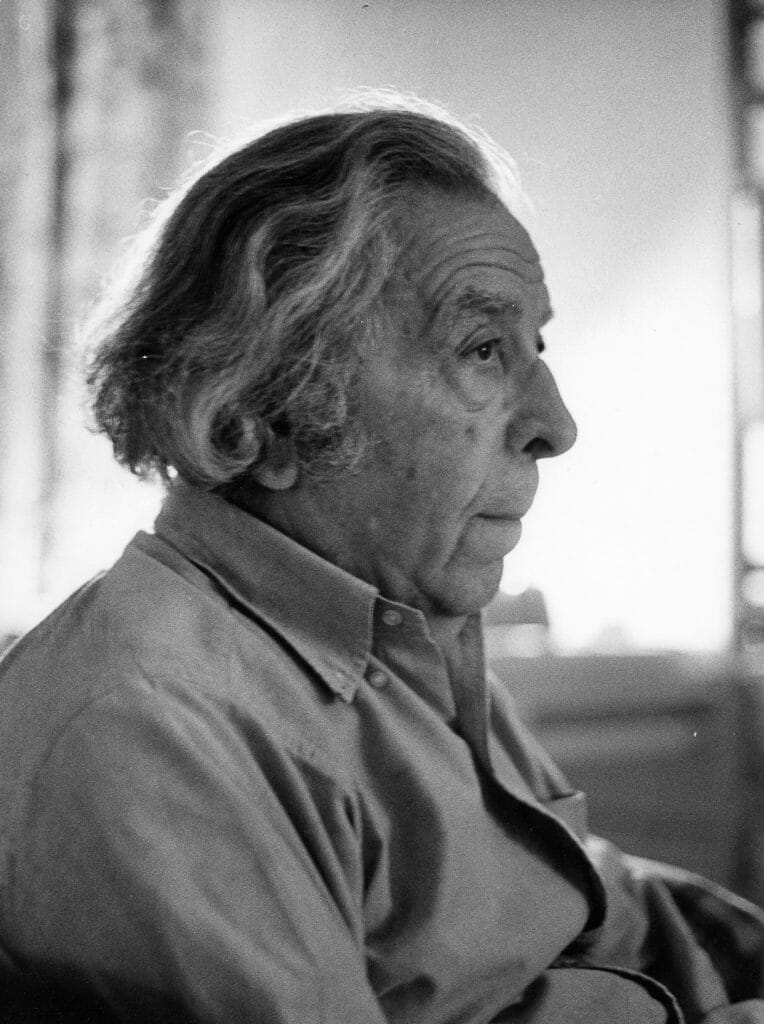

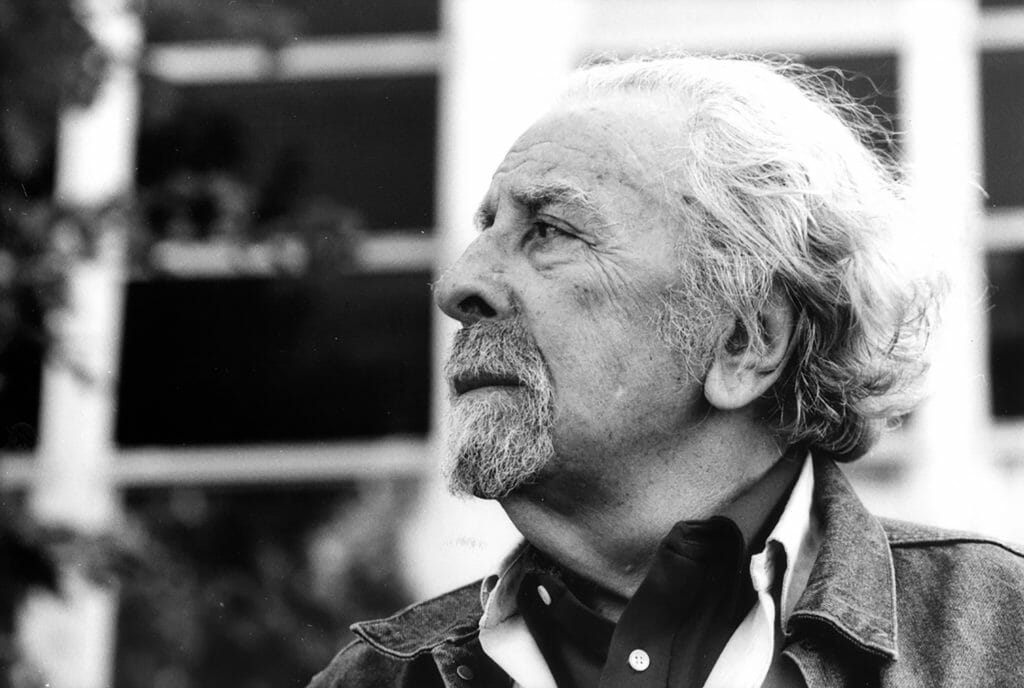

West End Avenue, New York

During his close to 70 year-long career in documentary films, Hurwitz, made upwards of 40 films and several important contributions to American film and television. He was central to the development of live television production style and technique as head of production at the nascent CBS Television Network in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s. In 1953, using an early portable sync-sound camera and recorder, he directed the first cinéma vérité film, The Young Fighter, for the CBS Television Omnibus program. He directed the television production of the Eichmann war crimes Trial, 1961, in Jerusalem, the first and still greatest televising of a trial. After continuing his independent filmmaking career for several years, Hurwitz was appointed chairman of the NYU Graduate Department of Film and Television in 1969, reorganizing the department and serving until his age-forced retirement in 1974. Returning to independent filmmaking, while filling appointments as artist in residence at several universities, Hurwitz made his final completed film Dialogue with a Woman Departed, 1980.

Because of the ideas in his films and writings, Hurwitz was blacklisted from work in movies and television, along with thousands of other left-wing Americans during the red-scare of the 1950’s. He refused to purge himself before the congressional investigating committees and could not return to work in television for 12 years. These years of political repression had the additional effect of hindering, for future historians, a full understanding of the innovation in documentary film in the radical 1930’s, and of Hurwitz’s films and contributions. In addition, Hurwitz’s fierce independence from the commercial trends in the documentary in the mid-20th century kept him on his own individual track. These two factors have tended to hold back his artistic works and contributions from wider appreciation and study. The purpose of this website is to help remedy this unfortunate gap in the knowledge of documentary history

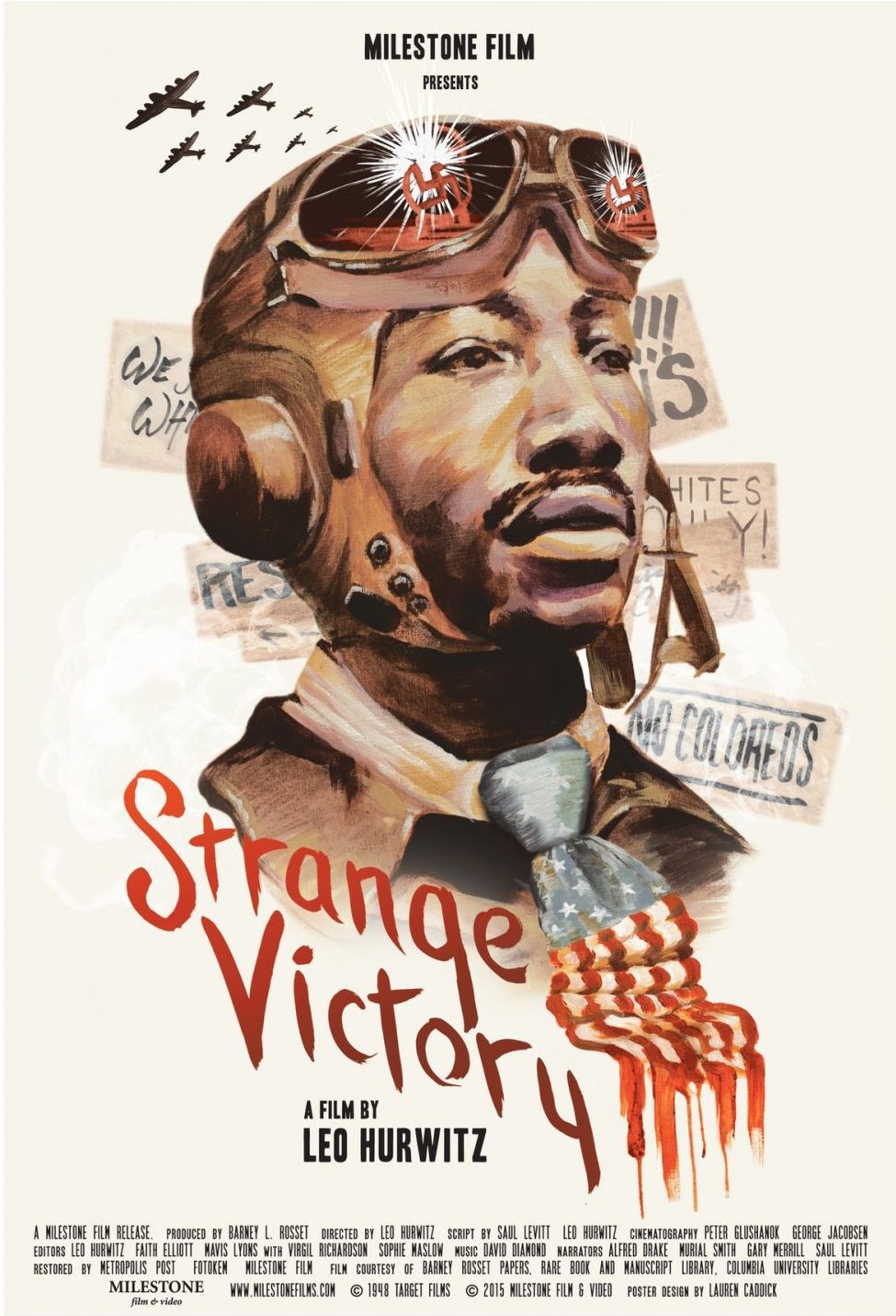

His films include: China Strikes Back, Heart of Spain, Native Land, Strange Victory, The Young Fighter, Museum and the Fury, Here at the Water’s Edge, Verdict for Tomorrow, Essay on Death, This Island, Light in the City, Dialogue with a Woman Departed

Family Background and Early Life

Leo’s family about a year before he was born. (l-r back row) Rosetta, Chava (mother), William, Solomon (father), Elizabeth, (l-r front) Peter, Sophia, Eleanore, Marie

Leo Tolstoy Hurwitz was born to immigrant parents in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, June 23 1909, the youngest of 8 children. His family had moved in steps, like so many in those years, first one father, then later a mother and 4 children sailing to this continent. The father, 17 years older than his wife of 24, came, determined to find education for his family. As a brother and two sisters were born here, the family moved to different streets in the crowded slum of the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and then across the bridges to the newer, still poor neighborhoods of Brooklyn where Leo was born, on Keap Street.

The name Hurwitz has its origins in Bohemia in the Carpathian Mountains, in the present day Czech Republic, in the 16th Century, when a Jewish trader seems to have taken it from a town named Hořovice. Several important rabbis and thinkers seem to have come in its line, as it moved to the intellectual center of Eastern Europe at the time, Vilnius (Vilna), Lithuania. It isn’t known how many bearers of the name and its many variants are true decedents of the original, since Jews took on surnames at different times and sometimes took those names from people they respected.

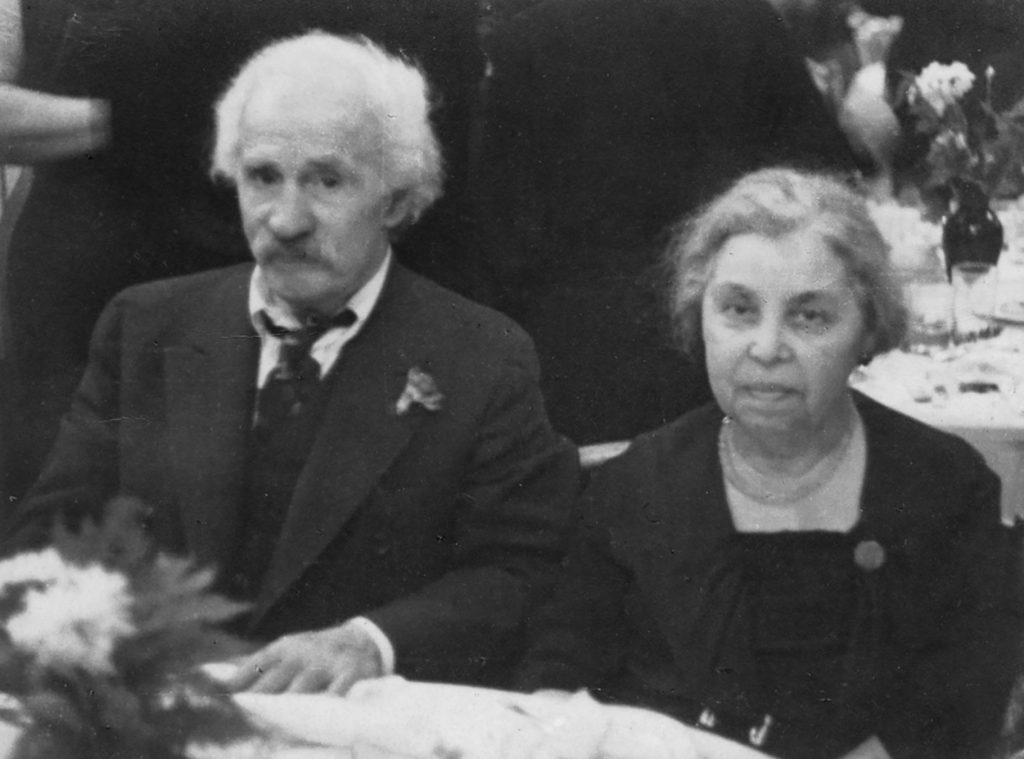

Leo’s Parents

Solomon Hurwitz (1860-1945), Leo’s father, was born in Vilnius. He was quite well educated. But since Lithuania produced more Jewish intellectuals at the time than it could employ, a common option for young men was to journey to another part of the Russian Empire and find work as a tutor. It was common for upper and middle class families to hire tutors, more so among more privileged, rural families in the Jewish Pale of Settlement in Byelorussia and The Ukraine. There, Jews were not allowed to attend local schools, often run by the church. However if they passed the entrance exams, the Gymnasium or official upper school was open to them. Solomon arrived in the vicinity of the tiny town of Rasava, south of Kiev and west of Dnieper River, to take up the work of tutoring the children of a local wealthy Jew. He soon found one of the few intellectuals in the area, Avrum Yankel Katcher, owner of a small grocery, and custodian of the town library of secular books. Katcher had traveled widely in Russia to buy for his store and had shaken off the rigid Hassidic beliefs of the elders of his town. It was rare for Jews to own books, other than religious ones, or to even speak Russian. As part of their broader-minded attitudes, Avrum and his wife Sarah had a practice of hosting visiting teachers and rabbis who came through their small town. As a newly arrived teacher, educated and Russian-speaking, Solomon held long discussions with Katcher, became friends and fell in love with his eldest daughter, Chava Riva.

Leo, at 4, at the door of the family apartment house on Keap Street.

They married, and soon moved to the nearby large river town of Kremenchug, Perhaps the idea of emigration was implicit in the marriage, spurred by the knowledge of how difficult it would be for this educated man to educate his own children in Russia. While in Kremenchug, they had four children while Solomon found only marginal success as a tutor. Soon, they made plans to leave for America. Solomon bought his ticket and arrived in New York in 1896. He was 41 and starting life over completely. For four years he saved his wages, earned, an intellectual unprepared for factory work, as a pushcart peddler and factory worker in the garment industry in Philadelphia and then New York City, toward bringing his family to New York. Soon, he was blacklisted from the garment industry for organizing strikes, and began a life as a tiny business owner (cigarette stands and the like) and dining table intellectual of some high regard. First an idealistic anarchist, he moved rightward after he failed to be appointed editor of Frei Arbeiter Stimmer (The Free Worker’s Voice), a large Jewish anarchist newspaper, founded by Johann Most. During most of Leo’s life, his father was a reform minded democratic socialist, a liberal Zionist, and a point for a son’s leftward rebellion.

In 1900, Chava and her four children, William, Elizabeth, Marie and Rosetta, traveled across Europe to Bremerhaven, then shipboard across the Atlantic and into New York Harbor among the flood of immigrants from Eastern Europe. Though anti-Bolshevik and life-long anti-Communists, both parents nevertheless attended socialist, anarchist, and trade-unionist meetings; they also sent several of Leo’s brothers and sisters to a socialist Sunday school. As the family gained four more children, it moved in the well-trod path, from New York’s Lower East Side to Williamsburg, where Leo was born, finally to a real house in Borough Park, Brooklyn, the youngest of the eight. His siblings included his eldest brother William Hurwitz, a small industrialist; Peter Hawley (né Hurwitz), an actor and theatrical manager, then union organizer, blacklisted in the 1950s; Elizabeth Delza-Munson, a dancer and movement teacher; Rosetta Hurwitz and Marie Hurwitz Briehl, both child psychoanalysts; Sophia Delza, a dancer turned Tai Chi master; and Eleanor Hurwitz Anderson, an executive assistant. It was an unusual and intellectually active family.

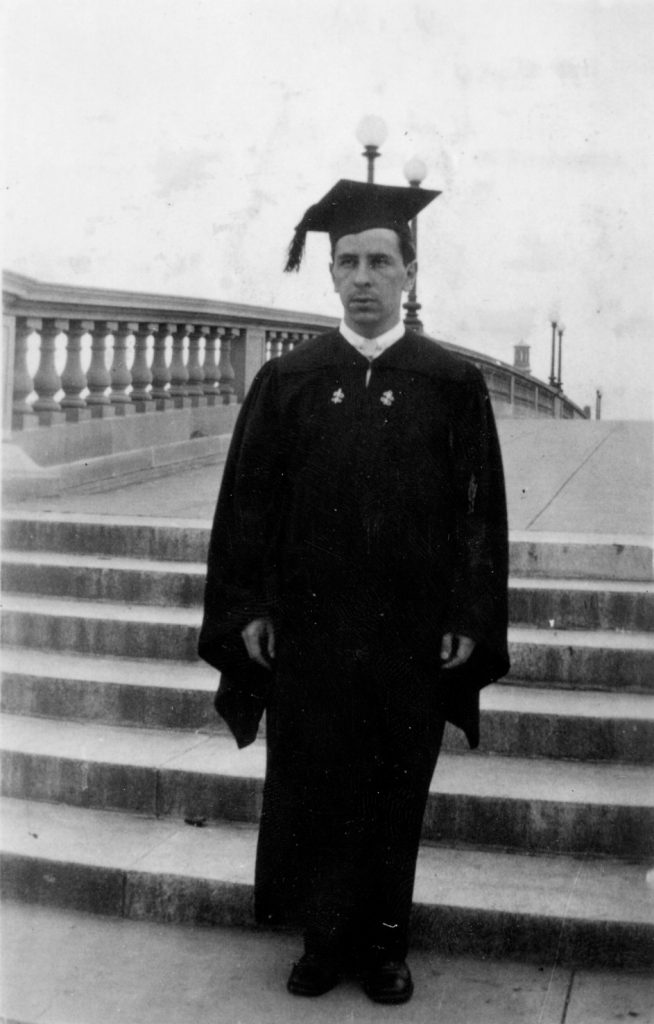

Leo graduates Harvard College

Leo, while being somewhat neglected by his tired mother, benefited from the attentions of his older sisters. He played the usual street games with his neighbors but he began to stand out intellectually in school. In the sharp and competitive world of the children of new Jewish immigrants, he began to distinguish himself. He attended Brooklyn’s Dewey Junior High School and New Utretch High School, where he was the editor-in-chief of the literary magazine The Comet and president of the dramatic society. He excelled in school. As he came to the end of High School, he was expecting, like his smartest friends, to attend New York’s City College, the target of the city’s working class. However, his sister Eleanor’s fiancé, a Harvard student, suggested that he sit for the exam for the Harvard Club Scholarship. There was one given each year. Leo won it. In the fall of 1926, he was steaming on the overnight Boston boat toward Cambridge and the next four years of explosive education.

The role of Harvard in Leo’s later life was somewhat unusual. It did not lead to a financially secure career as it might have for another child of immigrants, bent on tunneling upward. Four years in Cambridge gave him as rich an exposure to the life of the mind as one can imagine, a background in art history and philosophy, a time to turn a precocious high school intellectual into a real intellect. He graduated as the top student in the philosophy major, a department, the light of which was Alfred North Whitehead. He expected to get a fellowship to continue his studies in Europe – one that was uniformly given to the student who graduated top in his major. The fellowship was withheld that year. According to Leo’s tutor, Robin Field, the reason was anti-Semitism. Harvard, at the time, was keen to avoid the optics of having accepted Jews in large numbers. Leo did achieve Summa Cum Laude and Phi Beta Kappa honors at his commencement.

The Depression, and the Invention of the Social Documentary Film

Harvard degree in hand in 1930, Hurwitz graduated into the first plummet of the Great Depression. While at university, he had begun to feel that film, a new, yet increasingly powerful medium at the time, held some key to his future. Now, back in New York and needing to survive, he began a series of small jobs, a subway construction laborer (short lived), then a tie salesman (even shorter lived). He also began to gravitate to a world of other smart, often Jewish, young people who had begun to see the social inequities and economic cruelty of the capitalist system in the growing crisis. These sons and daughters of immigrants from Europe and from mid-America had grown to maturity in the relative boom years of the 1920’s. Upward mobility seemed real. Money seemed to be available to support a life in art, writing, music or photography. Now with the economic collapse, the future of an entire generation was foreclosed. Whole encampments of homeless men, “Hoovervilles,” grew up around New York. Hurwitz spoke of times when his entire fortune was the coins in his pocket.

As Leo Hurwitz began to enter the world of the arts in New York in the early 1930’s, what was ‘happening’ was the radical left.

In the conditions of the first years of the Depression, it was probably inevitable that Leo Hurwitz would turn toward radicalism. Socialist and anarchist ideas were alive in his community and had been debated at his family dinner table throughout his childhood. Now, the group that had formulated those ideas, systematized them into an understanding of causes and of a revolutionary goal, was the Communist Party of the U.S. At the time, the Party spoke in the clearest voice against the ills of depression America: for Civil Rights for African Americans, for the advancement of the labor movement, and in criticism of the shallowness of capitalist culture. For its members, it held out the revolutionary goal of a true egalitarian society, dreamed of by social reformers since the dawn of the industrial revolution. From the view of history, we can see that the CP-USA was hamstrung by its subservience to the dictates of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, its twists and turns of line. However at the time, its connection to Russia seemed, to Hurwitz and people like him, to add to its seriousness and to the viability of its aims. They believed that there was a real revolution in Russia, not just an idea but real socialism. Although making its revolutionary omelet might require “breaking some eggs,” Communist Russia had to be defended.

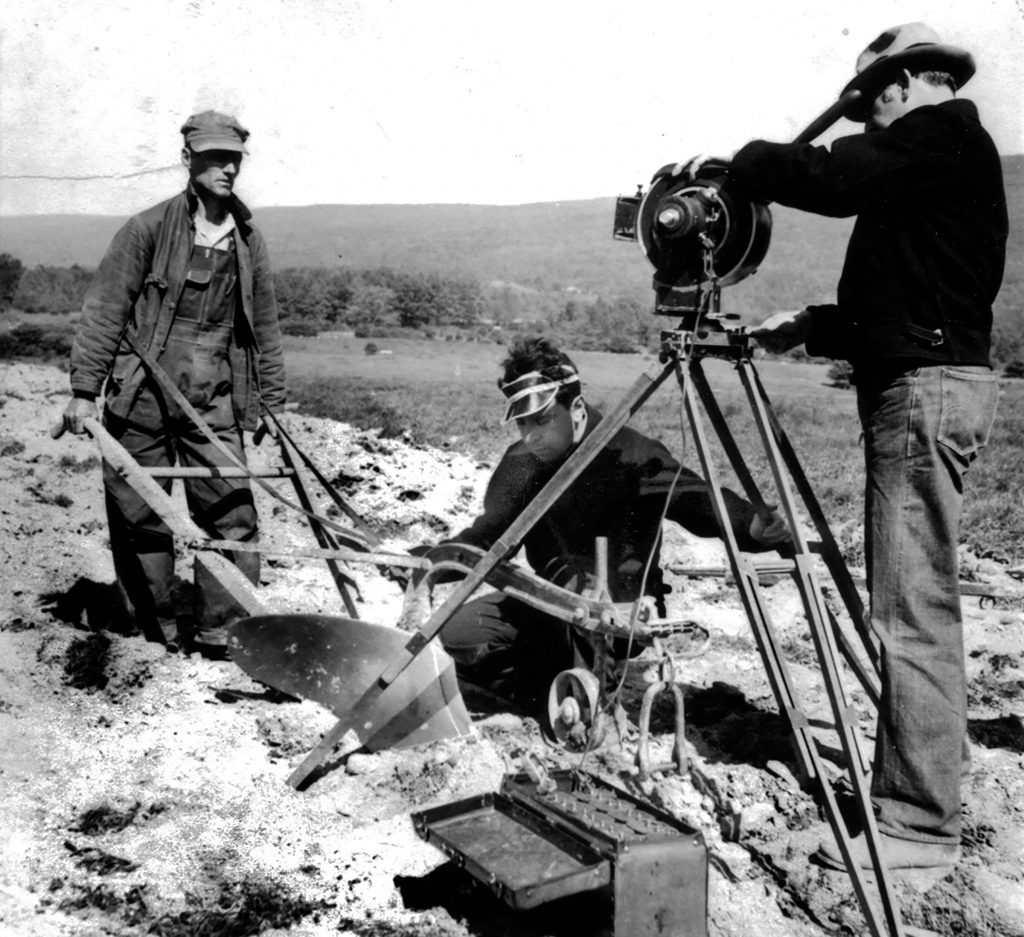

Hurwitz is at far left behind camera.

As Leo Hurwitz began to enter the world of the arts in New York in the early 1930’s, what was ‘happening’ was the radical left. The energy of young people with similar backgrounds to his – recent college graduates, intellectuals and artists – was toward social change and revolutionary thought. To support himself, Hurwitz began taking photographs for Harper’s Bazaar and writing book reviews for several New York newspapers, including the New York Post. He also worked for an emergency relief agency at an orphanage. Hurwitz left the agency after several months and began working without pay as an assistant editor for Creative Art magazine, where the husband of his sister Sophia, A. Cook Glassgold, was the managing editor. Hurwitz’s duties included securing copy and laying out pages of photographs by such photographers and avant-garde filmmakers as Ralph Steiner and Paul Strand, both of whom advised Hurwitz on his own photography. Steiner in particular taught Hurwitz the essentials of dark-room technique and photographic practice. Hurwitz also contributed film reviews to Creative Art. But due to a lack of funds and equipment, his own filmmaking activities were limited to working on ideas for short films and planning a feature-length animated adaptation of Alice in Wonderland.

In the early 1930’s Leo Hurwitz met and married Jane Dudley. At the time Jane had begun a career as a modern dancer. She studied first with Hanya Holme in the technique of Mary Wigman and then with Martha Graham, in whose company she became a powerful presence, premiering several solos. In the mid 1940’s she went on to form a trio with Sophie Maslow and William Bales and to choreograph several major pieces, the most celebrated of which was Harmonica Breakdown. Her work in the 1930’s and 40’s was marked by a deep commitment to social justice and leftwing causes. At the same time, its artistic merit was always clear to audiences and reviewers. During her over thirty-year marriage to Leo, she became a strong influence on his work, providing advice and support during periods of serious, if quiet self-doubt. They had one son, Tom Hurwitz. Dudley went on to become founding director of the London Contemporary Dance School, which was for thirty years the premier European educational institution in modern dance. Jane Dudley Obituary.

In late 1931/early 1932, Hurwitz’s interests in photography, film and radical politics led him to the Film and Photo League of New York, where he was soon joined by Steiner, filmmaker and editor Sidney Meyers, and Lionel Berman. In December 1932, Hurwitz filmed the National Hunger March on Washington, starting in Boston – Leo Seltzer, Samuel Brody, Robert Del Duca, and Steiner joined him at other points in the march – and later edited the footage into Hunger 1932 (1933). Additional Film and Photo League films on which Hurwitz worked as director, cinematographer, or editor include The Scottsboro Boys (1933) (in cooperation with the International Labor Defense) and Sweet Land of Liberty (1934) (with the Political Prisoners Committee of International Law).

In November 1933, the Workers Film and Photo League inaugurated the Harry Alan Potamkin Film School at the Lexington Avenue headquarters of the Workers International Relief. Named for the late film theorist and League member, the school was intended to meet the need for formal technical training and education in the history of film and film criticism. Hurwitz taught classes alongside other League members and soon advocated for the formation of a dedicated production unit within the League, a properly trained “shock troop,” consisting of “people who had a life-interest in film.” The idea met with resistance. Some members felt that forming a select cadre of filmmakers was elitist and ran counter to the idea of the League as a mass democratic organization. In response, Hurwitz formed NYKino in 1935. with Steiner, Meyers, Jay Leyda, Irving Lerner, and Ben Maddow, many of whom had comprised the core group of the Harry Alan Potamkin Film School. Initially funded by Hurwitz’s salary from New Theatre magazine, where he began working as managing editor in 1934, NYKino shifted away from the League’s strict adherence to actuality photography and the short film form. They began to incorporate dramatization and creative cinematography and editing into the depiction of real-life events. NYKino’s first projects included the completion of three films begun earlier by Ralph Steiner (Harbor Scenes, Quarry [a.k.a. Granite], and Pie in the Sky [1935]), all of which were edited by Hurwitz, as well as a dramatic March of Time-style newsreel “from a left-wing perspective,” titled The World Today, of which only two segments were produced (Sunnyside and The Black Legion). In 1935 Hurwitz, Steiner, and Paul Strand were hired by writer-turned-filmmaker Pare Lorentz to photograph the Resettlement Administration-sponsored film The Plow that Broke the Plains (1936) in Montana, Wyoming, and Texas. That summer, on July 2, 1935, Hurwitz also married the prominent dancer and choreographer Jane Dudley. As well as Leo maturing in his personal life, the documentary film movement in New York was also maturing.

Native Land, however, would prove to be Frontier Films’ most famous and influential work. It is a feature-length film that incorporates the full vocabulary of the documentary…

Upon their return from shooting The Plow That Broke the Plains, Hurwitz, Steiner, and Strand set about transforming NYKino into what Hurwitz would later describe as “an independent production company with day-to-day continuity and with a full-time staff.” Frontier Films was officially launched in March, 1937 with Strand as president and Hurwitz and Steiner vice-presidents. Steiner, along with Willard Van Dyke, would split from Frontier in early 1938 to form American Documentary Films. Frontier Films’ first completed production was Heart of Spain (1937) — based primarily on footage of the Spanish Civil War previously shot by New Theatre editor Herbert Kline and edited by Strand and Hurwitz — followed by China Strikes Back (1937); People of the Cumberland and Return to Life (both 1938); History and Romance of Transportation (1939); and White Flood (1940). In 1937 production also began on a feature-length film about American civil liberties alternatively referred to as “Production #5,” “Labor Spy,” “Edge of the World,” “Listen America!” and “Civil Liberties.” The film would take nearly four years to complete and would not be released until January, 1942, by which time it had been renamed Native Land. The departure of additional members, a depletion of funds, and the U.S.’s entry into World War II all contributed to the end of Frontier Films, shortly after the theatrical release of Native Land. That film, however, would prove to be Frontier Films’ most famous and influential work. With its cast of Group Theater actors, its music by Marc Blitzstein, photography by Paul Strand, narrated and sung by Paul Robeson, edited by Hurwitz, and directed by Hurwitz and Strand, it utilized the top talents of the New York arts scene. The film was the summation of the previous ten years of effort, film work and theoretical discussion. It is a feature-length film that incorporates the full vocabulary of the documentary, outstanding cinematography and editing, reenactment, archival footage, music and narration. Unseen by a wide audience because of the start of the war, it nevertheless remained influential within the documentary community over the next several decades.

World War II and CBS

As head of News and Public Affairs, Hurwitz was central to the invention of live television production in the nascent network

Rejected by the U.S. Army on account of a functional heart murmur, Hurwitz spent the early years of the war working on films for several government agencies, including the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (Song of Freedom, 1942, and There Shall Be Freedom, ca. 1943); the United States Navy Bureau of Aeronautics (Tomorrow We Fly, 1943); the Office of War Information (OWI) (Bridge of Men, 1943, and On the Playing Fields of America, 1944); and the British Information Services, for whom Hurwitz adapted British documentaries for American use. In general, however, work was increasingly difficult to find. According to Hurwitz, the OWI had grown leery of him: An expedition to the Arctic to film a sequence for the agency’s film Bridge of Men was canceled at the last minute due to an uncomfortable feeling that Hurwitz was a “premature anti-Fascist” one early indication that his involvement with Leftist politics was becoming problematic.

In 1943, after Hurwitz and Strand’s failed attempt to form a combat photographic unit for the Department of the Army, Hurwitz drove to Los Angeles in hopes of joining Frank Capra’s filmmaking unit of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Hurwitz had agreed to the unit’s use of footage from Native Land in Why We Fight: War Comes to America (1945), but his efforts to join the unit were rebuffed — another instance, Hurwitz suspected, of “red-baiting.” The film industry, however, proved more welcoming. After being shown Native Land by Hurwitz’s agent George Willner, David O. Selznick hired Hurwitz and Paul Strand on a 13-week contract to write and direct a shipyard sequence for the home-front melodrama Since You Went Away (John Cromwell, 1944). Hurwitz claimed to have shot over 40 minutes of footage, from which Selznick used only one shot.

While Leo Hurwitz spent around 9 months in Hollywood during World War II, he began an affair with Joan Laird that lasted into the early 1950’s. Under his teaching, she became an assistant editor and editor. They worked together on the post-production of the feature film, Salt of the Earth, released in1954.

After nine months in Hollywood, Hurwitz made his way back east, stopping first in Detroit to write a film for the United Auto Workers (a history of the union possibly titled “The Story of Democracy The Growth of a Union”). The film was never produced — Hurwitz suspected internal political problems — and by 1944 Hurwitz was back in New York City. Through his friend Gilbert Seldes, then director of CBS Television, Hurwitz was hired as a network producer, director, and writer. Hurwitz remained at CBS for three years, during which time he became director in charge of News and Special Events. At CBS, Hurwitz was central to the invention of the new art and craft of live, multi-camera television production.

Post War Production

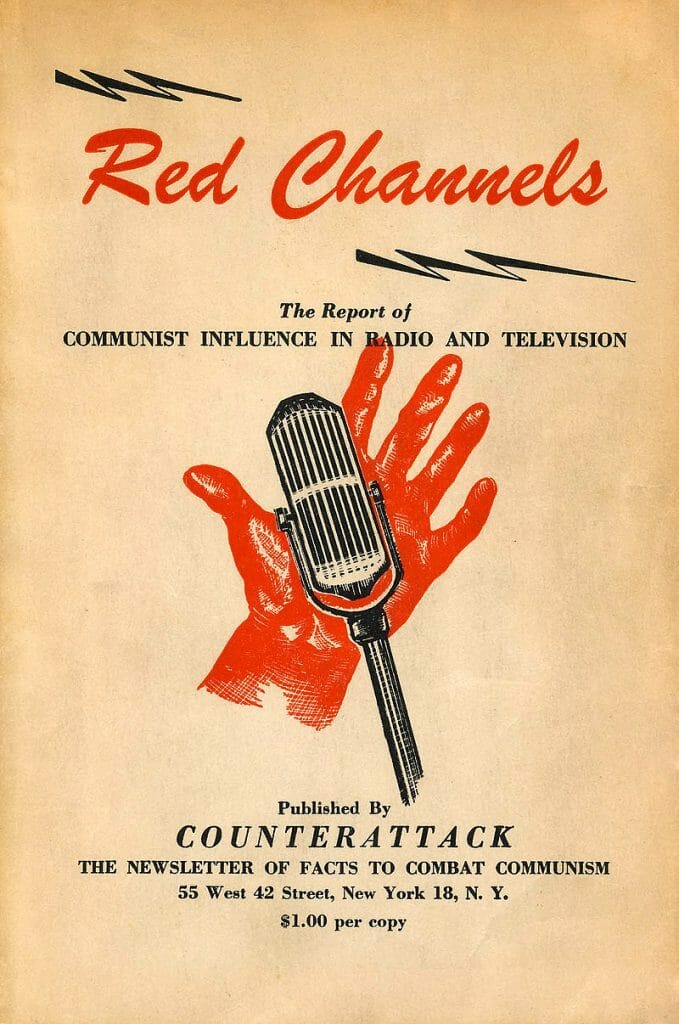

Shortly before the birth of his son, Tom Hurwitz, in 1947, Leo Hurwitz left CBS to direct his second feature-length film, Strange Victory (1949), for producer Barney Rosset’s newly founded Target Films. Originally titled “Candle in the Wind,” Strange Victory dealt with ongoing racial discrimination, including that faced by returning African-American veterans in post-WWII America. The film won first prize at the 1949 Karlovy-Vary Film Festival, but was criticized in the U.S. for its “communist undertones,” a critique which only strengthened many employers’ reservations regarding Hurwitz and his politics. These fears were formalized in 1950 when Hurwitz’s name appeared in the infamous anti-Communist publication Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television along with 150 other members of the entertainment industry who were suspected of anti-American ideas and activities.

Hurwitz’s unproduced projects of the period include feature-length adaptations of the novels Freedom Road by Howard Fast and Masters of the Dew by Jacques Roumain, and a film sponsored by Planned Parenthood. In 1949 Hurwitz proposed developing the “Movietel Camera,” a motion-picture camera linked to a remote television monitor that would enable a director to see what the cameraman sees through the viewfinder. The camera was never produced.

The Blacklist

Red Channels was the bible of the blacklist in film and TV. Published by a supermarket executive, with information leaked from FBI files, it detailed activities, like signing petitions or attending conferences, that labelled the subject, like Leo Hurwitz, politically untouchable by networks or studios.

Upon completion of Strange Victory, Hurwitz attempted to return to CBS but found the network unwilling to rehire him for staff or freelance work, an attitude Hurwitz attributed to his blacklisting. Over the next two years, work in television and films was more and more difficult to find, as the blacklist covered the broadcast and entertainment industries more and more completely. Hurwitz was ultimately hired as the Director of Television Production for the Souvaine Company, an independent production company headed by the composer and radio/TV producer Henry Souvaine. Hurwitz supervised the Souvaine Company’s hour-long adaptation of Bizet’s opera Carmen for the new CBS series Opera Television Theatre. (CBS seemed unaware of Hurwitz’s involvement.) Carmen debuted on New Year’s Day 1950, and though well-received, CBS’s inability to secure a single sponsor meant Opera Television Theatre‘s next production, La Traviata, also supervised by Hurwitz, would be its last.

In 1950 Hurwitz was hired by the United Nations Film Board to direct This Is the United Nations, a series of eight (though it appears the final number of issues was at least 15) theatrically released “screen magazines” highlighting the activities of the U.N. around the world. Hurwitz’s work for the Souvaine Company continued. In 1951 he re-edited and supervised the musical re-voicing and printing of Lou Bunin’s English-language adaptation of Alice in Wonderland (1951), a combination of live action and stop-motion animation originally released in France in 1949.

After 1951, Hurwitz would not work again in television for ten years.

In 1951 NBC hired the Souvaine Company to produce America Applauds: An Evening for Richard Rodgers, a 34-minute musical tribute to the popular composer sponsored by the United Shoe Company. While the broadcast was a critical success for the network – among its many featured performers was a young Mary Martin in her first television appearance – any future work with NBC was not forthcoming. Their reluctance was due, once again, to his blacklisting. That year Hurwitz also served as a script and production consultant for Prockter Productions’ television adaptation of the radio series The Big Story. The episode was to serve as an “audition film,” i.e. a pilot, for potential sponsor Pall Mall cigarettes and its parent company American Tobacco. Toward the end of 1951 Hurwitz was hired by Peter Lawrence Productions to adapt a stage production of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan for a Christmas Day broadcast on CBS-TV. Though Lawrence enjoyed success with a 1950 Broadway production of the play starring Jean Arthur and Boris Karloff, the broadcast was canceled when a sponsor failed to materialize. After 1951, Hurwitz would not work again in television for ten years.

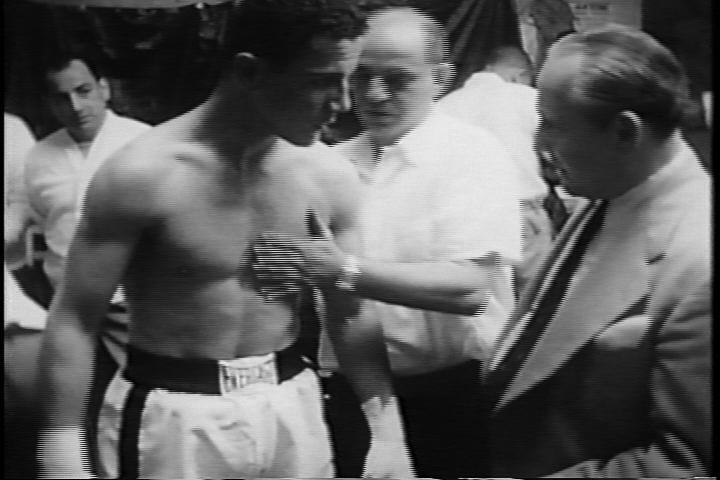

In 1952 producer Ben Gradus approached Hurwitz with a failed script written for the Health Insurance Plan of Greater New York and asked Hurwitz to rewrite and direct the film. The result, On this Day (1952), “dealt fundamentally with the anxiety that everybody feels… about the cost of medicine when you’re not insured,” and called for health insurance and socialized medicine. While working on the film, Hurwitz was approached by Look magazine photographer Fons Iannelli with motion-picture footage he had shot with his own 16mm camera and tape recorder which allowed for portable, synchronized sound recording. Iannelli shot the footage inside the emergency room of an urban hospital and asked Hurwitz to edit it into a coherent promotional film that could be used to interest potential investors and producers. The film, Emergency Ward (1952), clearly anticipated the Direct and Observational Cinema, or cinéma vérité movements of the late 1950s and early 1960s, and captured the interest of Robert Saudek, the producer of the CBS-TV’s Omnibus program. Saudek initially agreed to make at least one film with Iannelli’s invention. Unbeknownst to Saudek, the blacklisted Hurwitz would write, direct, and edit the film, a documentary about a young boxer in training who must also support a wife and baby. The Young Fighter aired on CBS in 1953 and is now considered the first broadcast example of direct cinema (cinéma vérité). Continuing to use Iannelli as a “front,” Hurwitz began production on a second Omnibus film about the Lexington School for the Deaf titled Deaf Boy, but left the project after a falling out with Iannelli (Hurwitz claimed Iannelli attempted to hijack the series by deliberately exposing him to Saudek). A follow-up film, possibly about the Dust Bowl, was canceled.

Trainers give instructions to Ray Drake,

In 1953 Hurwitz was invited to New Mexico to serve as a consulting director on The Salt of the Earth, an independently produced dramatization of the 1951 workers’ strike against the Empire Zinc Company that was written, directed, and produced by fellow victims of the blacklist. Hurwitz, however, soon grew frustrated with the quality of director Herbert J. Biberman’s footage and general disregard for Hurwitz’s advice. He returned to New York City before the film was completed but eventually went back to assist with the editing, in a secret cutting room in Topanga Canyon, California. Further disagreements led to Hurwitz once again exiting the production, leaving most of the editing to be done by Ed Spiegel and Hurwitz’s assistant, Joan Laird.

When support failed to materialize for Hurwitz’s planned film adaptation of The Lonesome Train, Millard Lampell and Earl Robinson’s folk oratorio about Abraham Lincoln, Hurwitz took over the directing and editing of Freedom of the American Road (1955), a film sponsored by the Ford Motor Company and produced by MPO Productions. Hurwitz also served as a consultant on a film for the New Jersey Railroad Association [title unknown] and The Earth Is Born (1956), the first in a projected series of short films based on the Life magazine science series The World We Live In.

In 1956 Hurwitz received funding from Film Polski to make The Museum and the Fury, one of the earliest films to deal with the horrors of the Nazi holocaust. Granted access to the Polish film archives, Hurwitz was expected to make a film addressing the general effects of World War II on Poland. Hurwitz, however, focused instead on the destruction of Polish Jewry and Poland’s concentration camps-turned-museums. Ultimately, he produced a great film that, while concentrating on The Shoah, links genocide to the broad human experience of war and violence. Finding the finished film too poetic, Film Polski refused to distribute it but allowed Hurwitz to purchase the rights for $5000.

In 1955 Hurwitz was once again called upon to rescue a troubled film project, this time a U.S. travelogue sponsored by Pan American Airways and produced by Henry Strauss. U.S.A. was Pan Am’s first film intended to lure foreign travelers to the U.S., but the project had become stalled for nearly a year and a half. Under Hurwitz’s direction, the finished film incorporated travel information with subtle satire, and introduced the formal technique of moving the camera across drawings and still photographs that would, decades later, become associated with the documentary style of Ken Burns. U.S.A. went on to win several international awards. The prestige delighted Strauss and Pan Am, who wanted Hurwitz to direct several films in Japan. But U.S.A. would be the only film Hurwitz would direct for Pan Am: His political leanings and resultant blacklisting rendered him ineligible for a U.S. passport (although he would go on to write Pan Am’s 1958 short Voici la France).

Still from Dialogue with a Woman Departed

Returning to sponsored films, Hurwitz soon found work with Dynamic Films, for which he wrote two sponsored films: Pattern of a Profession (1959), which Dynamic Films produced for the American Dental Association, and Gift of Years (1960) for the National Committee on Aging. The first in a planned series titled Preparation for Retirement, Gift of Years was completed without Hurwitz’s involvement: Having written a script, he left the project when rewrites were requested.

In the mid 1950’s, Hurwitz began a long affair with Peg Lawson, first his assistant editor and then a great editor in her own right. After Leo’s separation and divorce from Jane Dudley in 1964, Leo began a living and working partnership with Lawson, during which they collaborated on more than half a dozen films. He considered her his muse and the love of his life. Her death from cancer in 1971 led Hurwitz to begin work on a film about her and his thoughts and emotions about her life and death. It was to become his last great work, Dialogue with a Woman Departed.

The Eichmann Trial

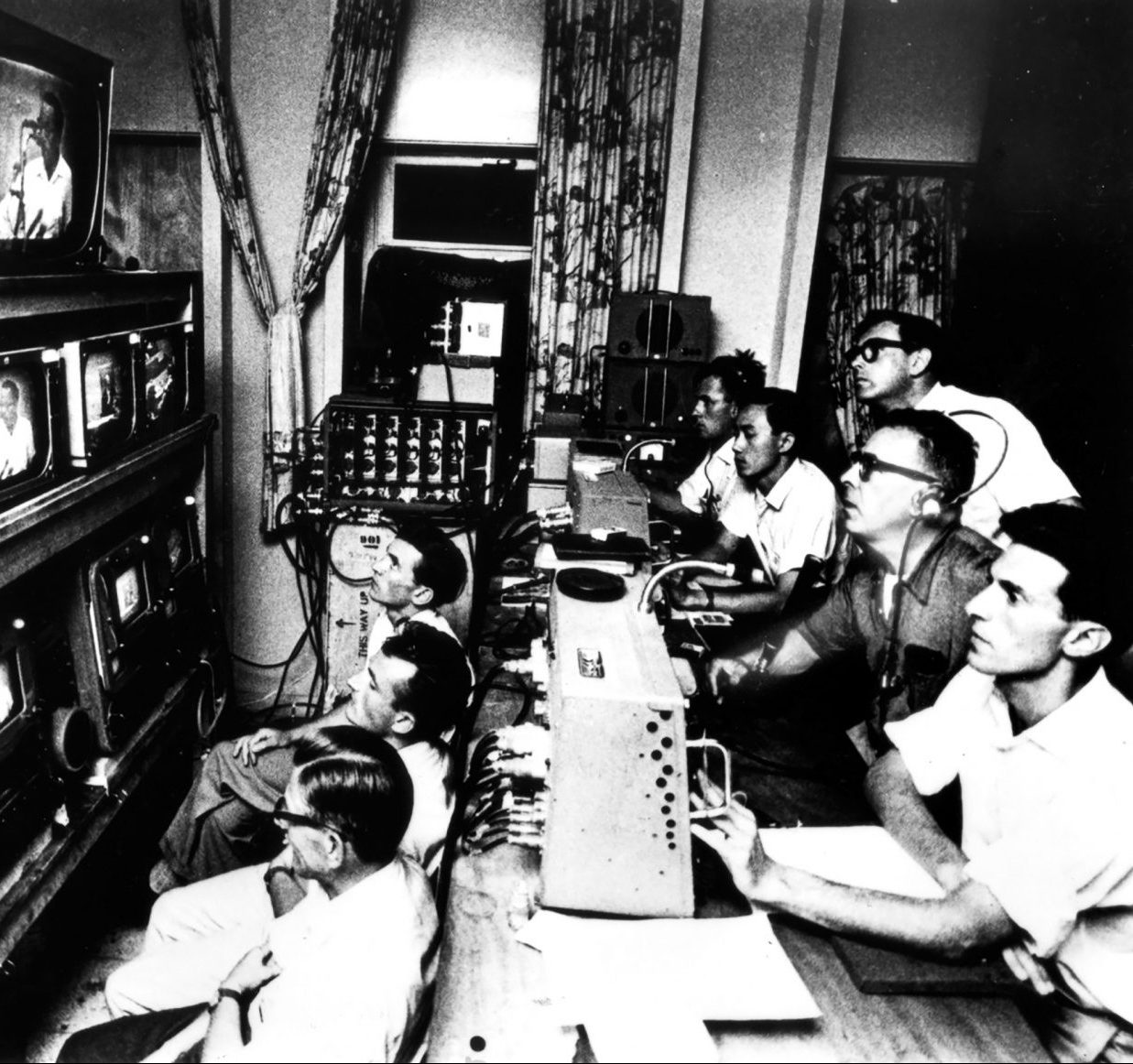

The control room of the television coverage of the Eichmann Trial in Jerusalem. Leo, the director, is center with dark shirt. Milton Fruchtman, the producer, is standing.

In late 1961, Hurwitz returned to television after contacting Milton Fruchtman, the chief producer at Capital Cities Broadcasting, a small network partially owned by Lowell Thomas. Fruchtman had secured the exclusive rights to videotape the trial of the captured SS officer Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, but he faced a personnel problem: the agreement stipulated the use of Israeli cameramen in the courtroom. All of the new camera operators would have to be trained in the use of television cameras, since Israel at the time had no television industry. Hurwitz’s activities at CBS often included training television crew members. Having finally been permitted a U.S. passport, Hurwitz arranged for Fruchtman to see his Holocaust-themed film The Museum and the Fury. Impressed, Fruchtman hired Hurwitz to direct the continuous television coverage of what would become a historic, nine-month exposé of the Nazi bureaucracy of murder and the horrors of the concentration camps. Since Capital Cities was the sole provider of pool video-recording of the proceedings, Hurwitz’s footage of the trial would be sold to television news outlets and then broadcast throughout the world. It was responsible for changing attitudes toward the holocaust in all of Europe, especially Germany, and in the U.S. as well. Filled with innovation, the project remains the greatest visual document of a war-crimes tribunal. Afterwards, Hurwitz oversaw the editing of trial highlights into Verdict for Tomorrow (1961), a 30-minute summation which won a Peabody Award.

Later Film Production – NYU Graduate Film Department

Hurwitz explains a shot to camera assistant, Peter Eliscu and 2nd cameraman D’Arcy Marsh. Production still, Essay on Death

Back in the U.S, Hurwitz revisited a film he had all but completed before leaving for Jerusalem: Here at the Waters’ Edge (1961), a visual poem about the sights and sounds of New York Harbor, co-directed by the photographer Charles Pratt. Hurwitz now felt the film needed to be more concise, and edited out some 15 minutes of footage as well as the haikus he had composed for the voice-over soundtrack. In addition to the film, Hurwitz released an edited version of the soundtrack on Folkways Records titled Here at the Waters’ Edge 1: A Voyage in Sound (1962). Hurwitz recorded material for a second soundtrack album — selections from the writings of Walt Whitman, Hart Crane, Herman Melville, Alan Dugan, and Thomas McGrath, read by Melvyn Douglas over ambient harbor sounds — but it was never released.

Though still blacklisted from the television networks, Hurwitz was able to find work at National Educational Television (forerunner of PBS), once again though Gilbert Seldes, who had left CBS and was working for the public television network. Seldes advised Hurwitz to stay away from political and public affairs and concentrate on cultural affairs programming. One of the first projects Hurwitz was asked to write, direct, and edit for NET was Essay on Death: A Memorial to John F. Kennedy (1964) commemorating the first anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination. The film was co-written by NET producer Brice Howard and co-edited by Peggy Lawson, a long-time assistant with whom Hurwitz had begun a relationship. He separated from Jane Dudley in 1964.

Hurwitz sets up a shot. Production still, Essay on Death

While never hired to the NET staff, Hurwitz went on to write, direct, and produce the acclaimed documentaries The Sun and Richard Lippold and In Search of Hart Crane (both 1966) for the network, all the while attempting to raise funding for such independent projects as a feature-length adaptation of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The Scarlet Letter.

In 1965 Hurwitz directed and produced Haiku, a 30-minute dance film featuring Jane Dudley’s choreography. The same year a decision was reached in Hurwitz v. Directors Guild of America Incorporated, a lawsuit Hurwitz and five other plaintiffs brought against the Directors Guild of America (DGA) regarding the non-Communist loyalty oath required by the union for membership. The plaintiffs, originally members of the Screen Directors International Guild (SDIG) which had no such requirement, refused to sign the oath when the SDIG merged with the DGA in 1965. The DGA in turn refused them admittance into the union. In July 1965 the U.S. Court of Appeals decided the oath was “vague” and forbade the expulsion of anyone who refused to sign it.

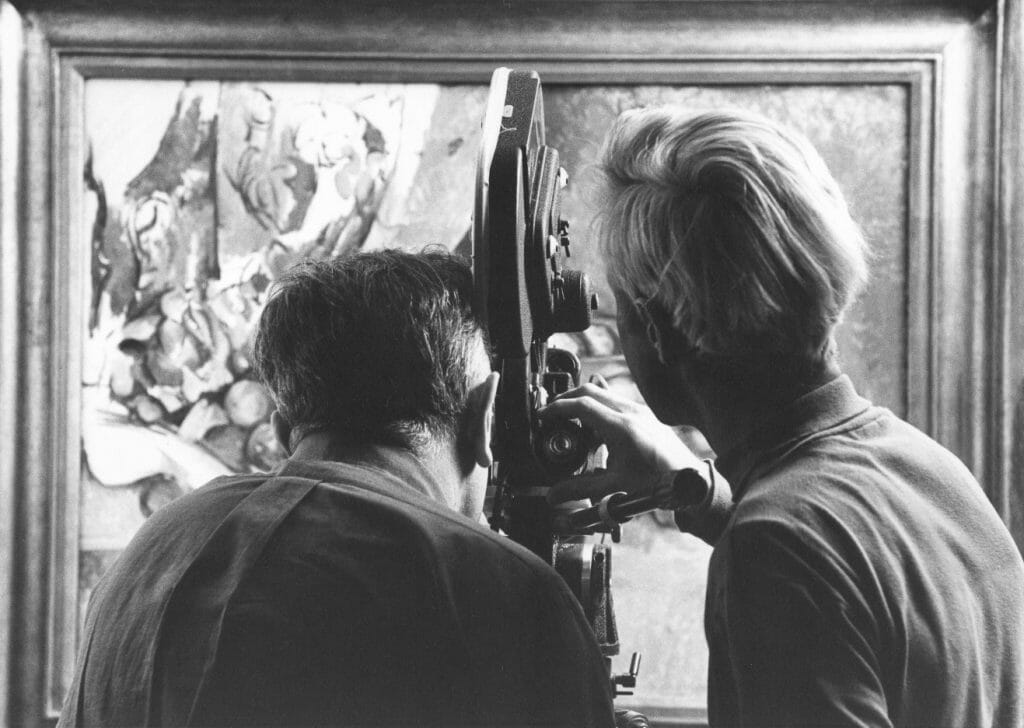

Leo and Manny Kirchheimer film Discovery in a Painting. Production still. Kirchheimer finished the film in 2018

After a brief return to political filmmaking with Do You Know a Man Named Goya? (1967), a two-minute anti-Vietnam War film screened as part of the 1967 “Week of the Angry Arts” anti-war festival in New York City (one of approximately 12 films selected to tour the country), Hurwitz returned to “cultural affairs” with a series of four films about visual perception, collectively titled The Art of Seeing. Sponsored by the American Federation of Arts (AFA), and with the psychologist and film theorist Rudolf Arnheim serving as consultant, The Art of Seeing includes the shorts Light and the Country, Light and the City, Discovery in a Landscape, and Journey into a Painting. Light and the Country and Light and the City were originally excerpted from a longer film titled World of Color. Journey into a Painting also exists in a longer version titled Discovery in a Painting (completed by Manfred Kirchheimer in 2015). Hurwitz continued his exploration of the visual arts with This Island (1970), a short film about the Detroit Institute of Arts that was sponsored by the museum. The film was shot over the summer of 1969 but its completion was complicated by Hurwitz’s July appointment as Professor of Film and Chairman of the Graduate Program in the Institute of Film and Television at New York University (NYU).

While still at NYU, Hurwitz began work on the film that he would consider his magnum opus, Dialogue with a Woman Departed.

Beginning in 1936 when Hurwitz first taught a course in “photo-sociology” at Sarah Lawrence College with the developmental psychologist Lois Barclay Murphy, Hurwitz almost continually held classes and seminars in filmmaking and television production at colleges, universities, acting schools, and even his own home. His hiring by NYU, however, was Hurwitz’s first long-term, full-time appointment by an academic institution (the person he was hired to replace was his erstwhile Omnibus producer Robert Saudek). Hurwitz remained at NYU until the end of the 1974 spring semester when he was forcibly retired. A controversial new policy had lowered the retirement age to 65.

Peg Lawson was Hurwitz’s second wife and collaborator

While still at NYU, Hurwitz began work on the film that he would consider his magnum opus, Dialogue with a Woman Departed. Part tribute to Peggy Lawson, who died from thyroid cancer in 1971, and part examination of key events of the 20th century, the four-hour film incorporated archival footage from different sources as well as material from Hurwitz’s own work. With the help of his new partner, Eleanor Burlingham, Hurwitz spent much of the remaining decade exhibiting the film as a work-in-progress. At the same time as tirelessly pursuing funding for its completion, he taught film courses and seminars at Kirkland College, the University of Iowa, and the State University of New York at Buffalo. Once completed, Dialogue with a Woman Departed opened to unanimously favorable reviews and was often the centerpiece of international festivals and career retrospectives.

Eleanor Burlingham, whom he had met during an artist-in-residency at Kirkland College (now part of Hamilton College), was originally a poet, who found her way to a medical career in psychiatric practice. She lived with Leo during the final period of his life — his travels to screenings, lectures and retrospectives throughout Europe and the US, and then his unfinished writing of a script on the life of John Brown. She died from cancer in 2019.

In 1988 Hurwitz brought suit against the United States of America and the Central Intelligence Agency when, after requesting his file from the CIA in August 1987, he discovered that a letter he had written to John Howard Lawson in the Soviet Union in 1963 had been opened and photocopied by the agency. Hurwitz cited an invasion of his privacy, but the case was dismissed by a U.S. District Court on the grounds that Hurwitz had failed to state a claim upon which relief could be granted; in addition, the two-year statute of limitations had been reached. In 1989 the judgment dismissing the complaint was affirmed by the U.S. Court of Appeals.

In the 1970’s and 80’s Leo traveled often to film communities, conferences and festivals in Europe, where his work was much more appreciated than in general in the US.

As early as 1980 Hurwitz had begun work on what would be his final film project: “In Search of John Brown,” an exploration of the life and influence of the American abolitionist. Hurwitz had already completed extensive sequence outlines and script drafts when he was diagnosed with cancer of the colon.

Leo Hurwitz died on January 18, 1991, in New York.

(Partial text for this biography courtesy George Eastman Museum)